WHO?

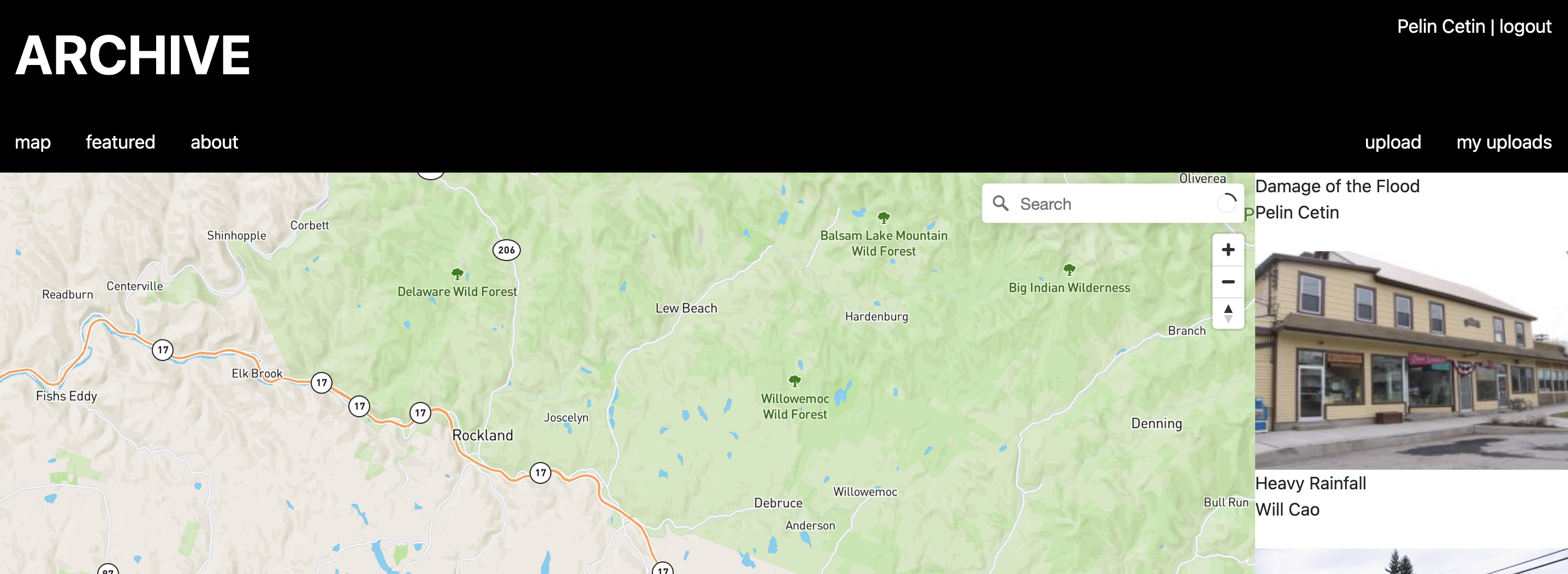

Livingston Manor, a small town on the edge of the Catskill Mountains with just over 1,233 residents in 2018 serves as our case study for this project. Livingston Manor only has one newsroom and one library, so it’s both a news and library desert. The town’s only newspaper is run by two adults and five high school students. Today, news and knowledge about the town is captured and recorded only by this grassroots newsroom.

WHAT?

The origin of the word Palimpsest is used for something reused or altered but still bearing visible traces of its earlier form. It can be used for material documents as well as larger scale urban lanscapes. Our project acts as a bridge between the physical and the the digital, lost historical data and community members by allowing them to share archival pictures on our platform.

WHY?

Our main PIT goals are to connect residents together and create relationships within the town

community with knowledge distribution. The content is moderated by the community and aims to increase the historical archives of the town. Through a digital

platform, the project hopes to create a community identity for Livingston Manor.

STATEMENT

Our solution, "Palimpsest", introduces a prototype that encourages communities to share their moments and their local history. The act of sharing memories allows for connections to be drawn between community members and creates a sense of belonging and unity within the neighborhood.

Their responsibility to capture and preserve community knowledge, prompts our question:

How might we help Livingston Manor record

and engage with their shared history so that

community members have a greater sense of

identity, belonging, and unity?

DEFINING PIT

For our team, we came to understand the “public interest” component of public interest technology is always authored by the people and never by the technology. Regardless of the product or service developed, a group of passionate and dedicated members from within each community would be required to define and promote public interest. Instead of technology developed for the public interest, we needed to shift our thinking of PIT toward technology developed to facilitate the work of people promoting public interest.

Additionally, public interest technology must go beyond building yet another tool to accomplish a task. Although commercial products may succeed by prescribing a certain task for a certain niche of people, we found the task-oriented view obscured and robotized the underlying needs of communities and were uncritical of the systems that make that task necessary. Moreover, we found the needs of the communities we spoke with could not be generalized into a single process.

Outside of geographic and social relationships, a community can often be more diverse than not. In our case, PIT additionally meant creating an equal platform where many members of the community could express themselves, rather than specifying a single process as representative of the whole.

INTEREST BEING SERVED

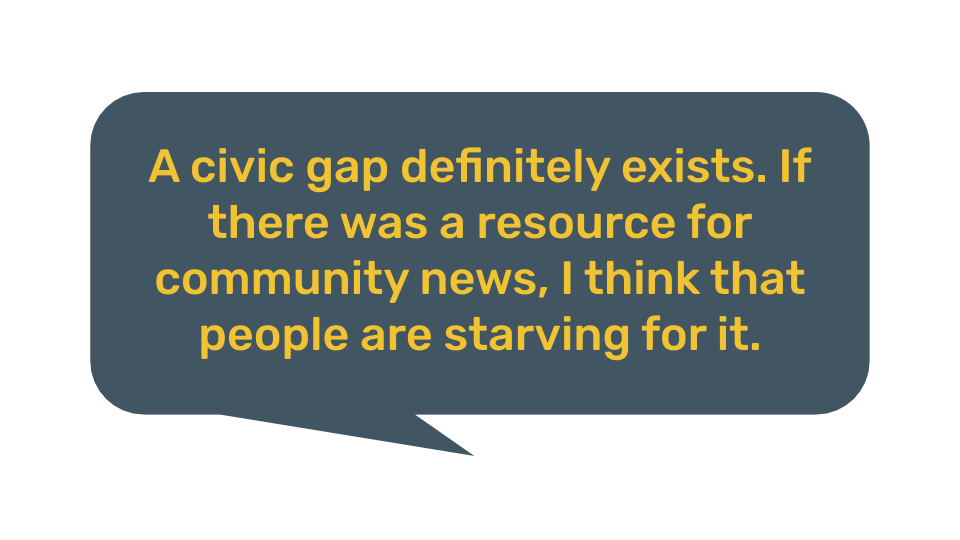

In our interviews with KCQ and ManorInk, we found the most successful stories with the most engagement were not necessarily breaking news, but instead offered a deep dive into local stories and history that added an additional dimension to familiar places. A reference librarian at Cook Memorial Library, where a COVID-19 archive was launched in the spring, stated that she believed there was a hunger for many more similar projects in the future.

Through these same projects, we realized the many community members are more than happy to share. Community members regularly updated Cook’s Memorial COVID-19 archive over the months following its launch, and KCQ noted the articles often prompted further questions, or even encouraged community members to assist in more challenging research, such as tracking down a one-of-a-kind car.

We hope to offer a means to bridge these two community needs, offering a means to connect residents together and create relationships within the town, increase the richness of historical archives of the town, and create a community identity for Livingston Manor.

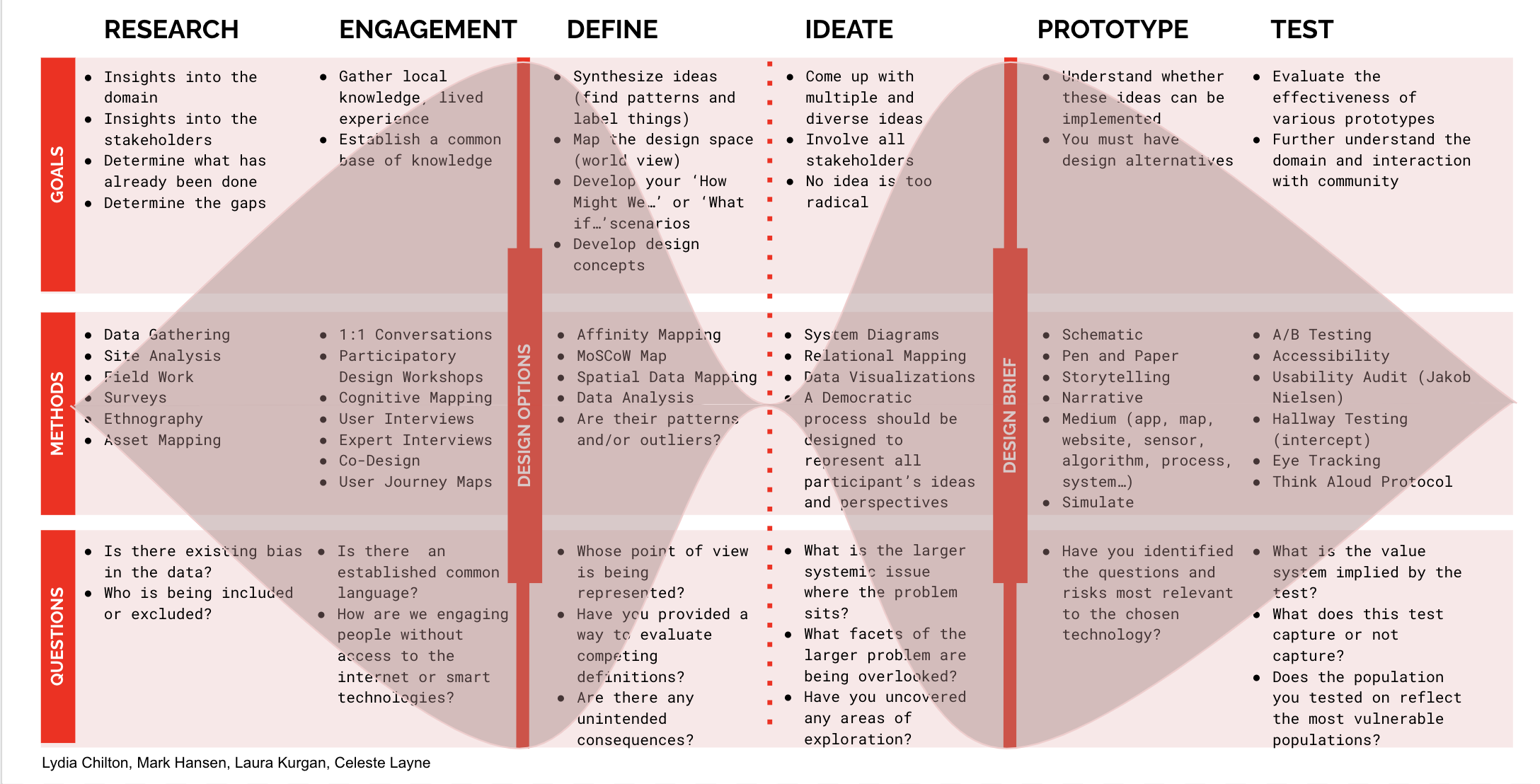

RESEARCH

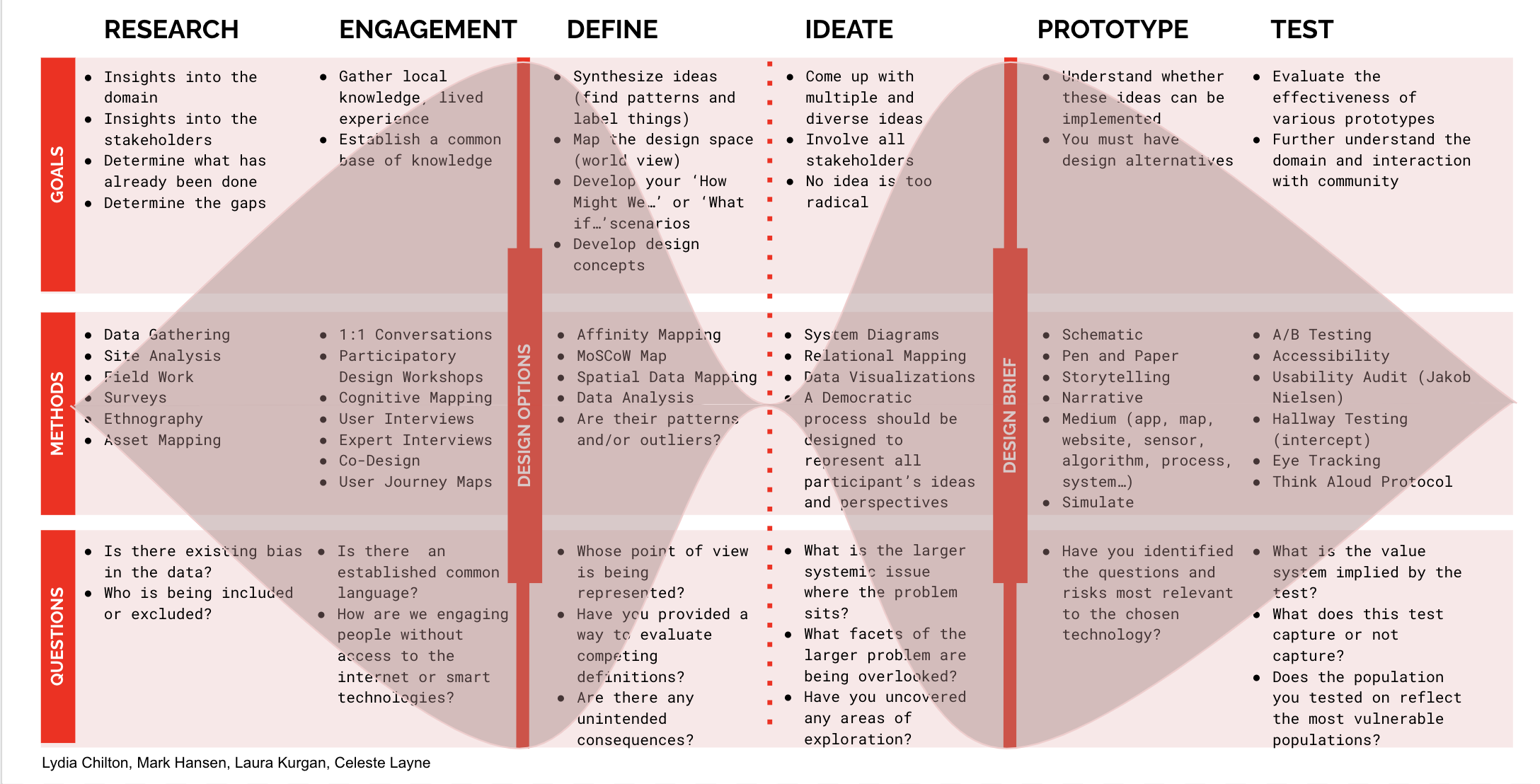

Double Diamond Process

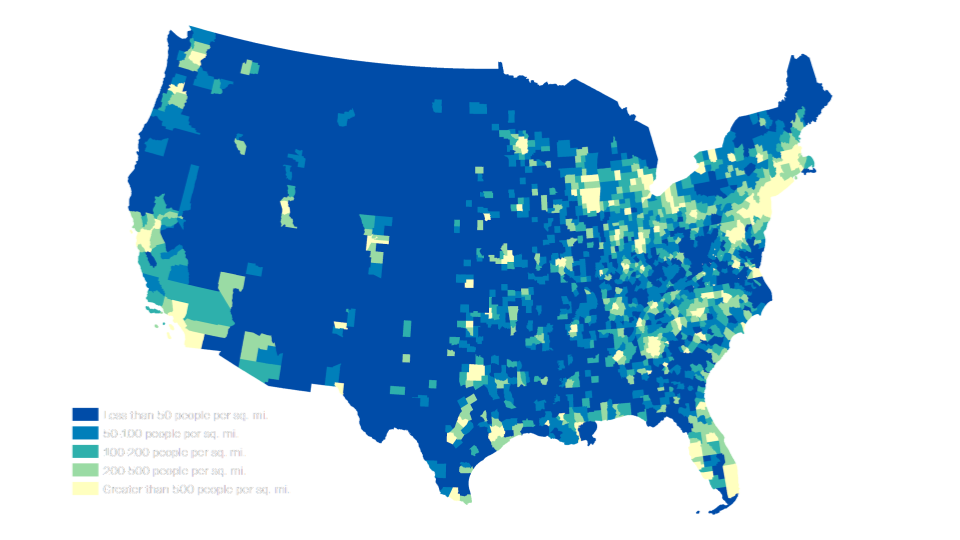

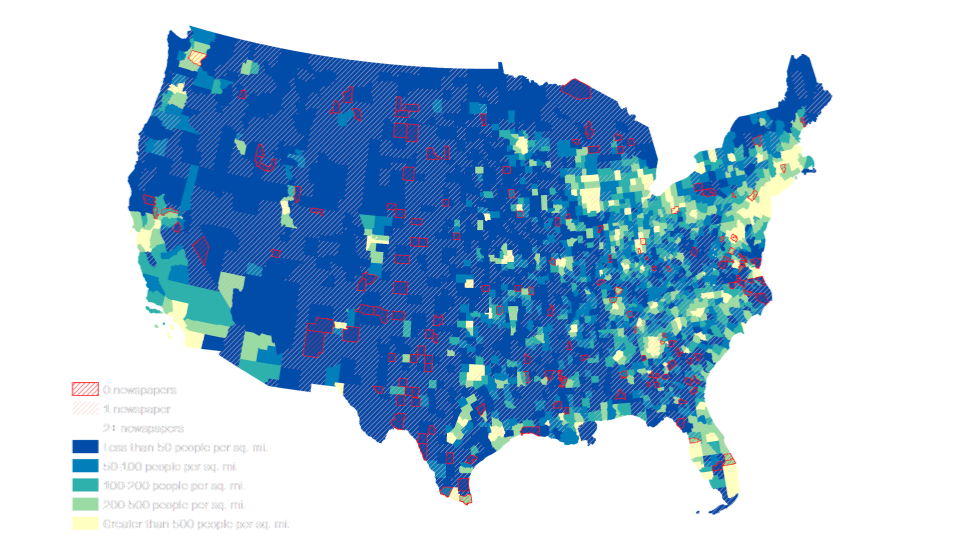

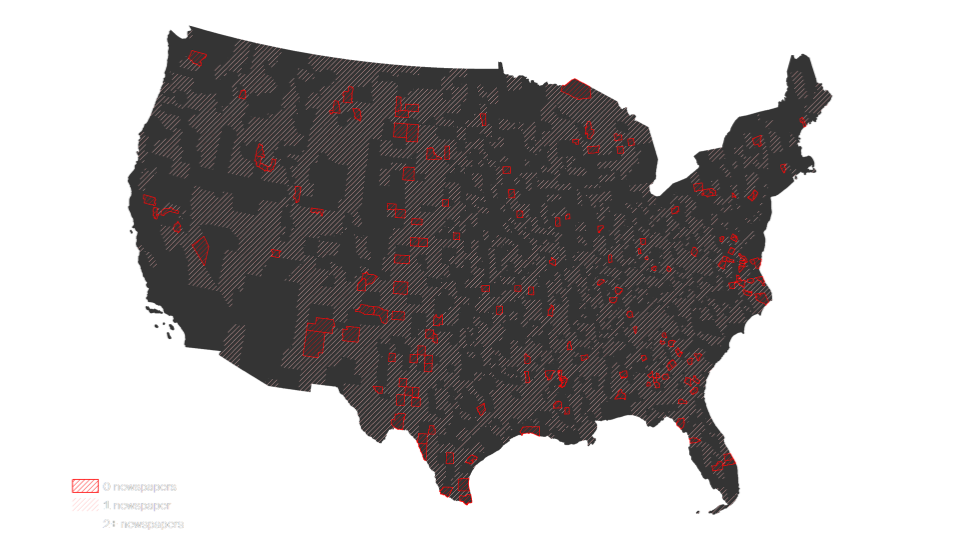

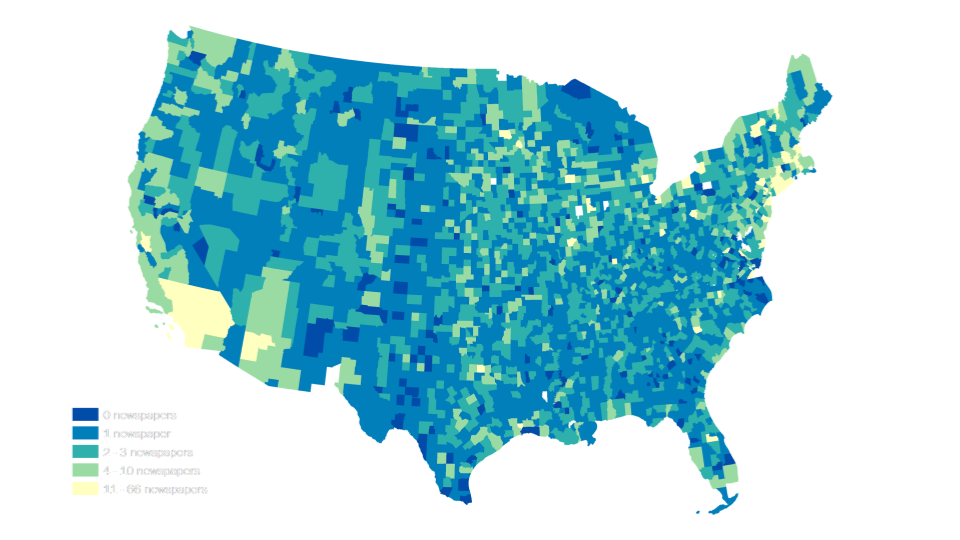

News deserts are communities with limited access to credible and comprehensive news -- are especially prevalent in

rural America.

More than 500 of the 1,800 newspapers that have closed or merged since 2004 were in rural communities.

In a report released earlier this year, the Pew Research Center found that about half of U.S. adults (47%) say the local

news they get mostly covers an area other

than where they live.

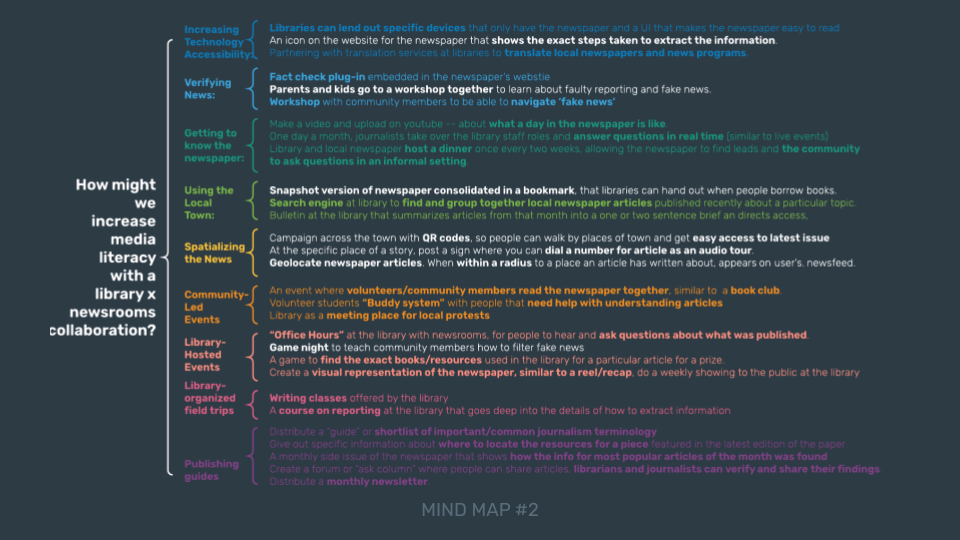

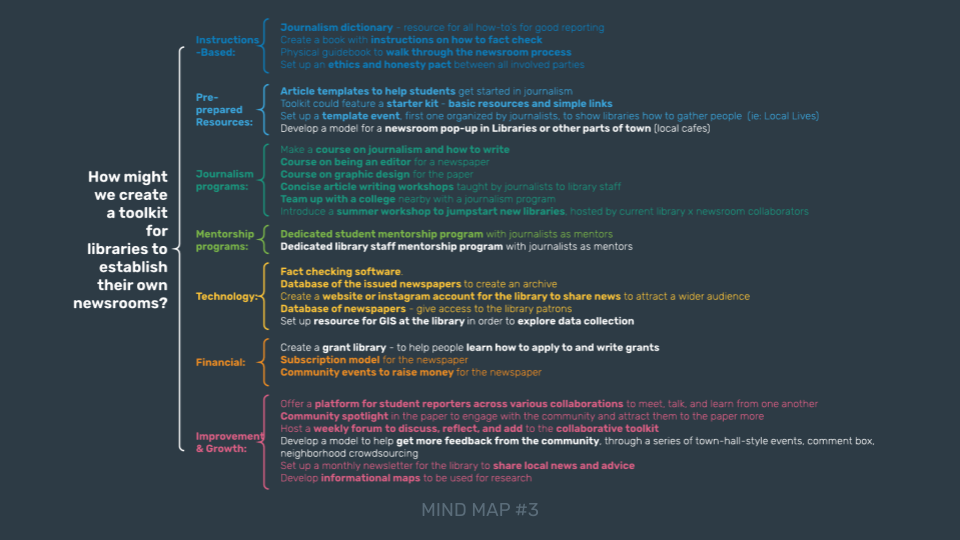

LIBRARY X NEWSROOM COLLABORATION

From our interviews with KCQ, NowCastSA, and Local Lives, we realize that both libraries and new organizations play an important role in

providing information to a community. Newsroom often write the first draft of a community's history, while libraries preserve its access.

A recent

Pew Research Center

poll found that most Americans feel that libraries can help them find reliable, trustworthy information.

Libraries and news organizations tend to have a lot in common — they provide information, they’re a vital community resource — but also because both institutions are in the process of completely reinventing themselves.

Many of the media outlets that remain are under attack for allegedly peddling fake news. It’s a problem that journalists alone cannot fix. Local libraries are pushing to restore people’s faith in the media.

In some towns, one institution manages both these roles. We collaborated with Manor Ink, a youth-led new organization in Livingston Manor.

Livingston Manor's previous newspaper publication ceased in 2009, a victim of the Great Recession. In 2012, Manor Ink was founded and is currently run by two adults and five high school students. Today, news and knowledge about the town are captured and recorded only by this grassroots newsroom.

Through our interview process, we’ve had the chance to talk to and learn from many newsroom x library collaborations, including the Kansas City Star about their “What’s your KCQ?” project. In this project, reporters and librarians answer reader questions together.

The aim is to teach community members how to locate and access information using library resources, while also highlighting how reporters uncover information through public records, interviews and other journalistic methods. It infuses transparency and engagement into an impactful collaboration.

Savannah, who is a journalist at Kansas City Star, said that the Kansas City Star and the Kansas City Public Library have a special collection together that inspired the KCQ project:

the Missouri Valley Special Collections. The special collection has thousands of digitized photographs and material related to the history of Kansas City, and the community members can interact with them at their convenience.

Our connection with the KCQ has inspired our project and now acts as a precedent for Palimpsest.

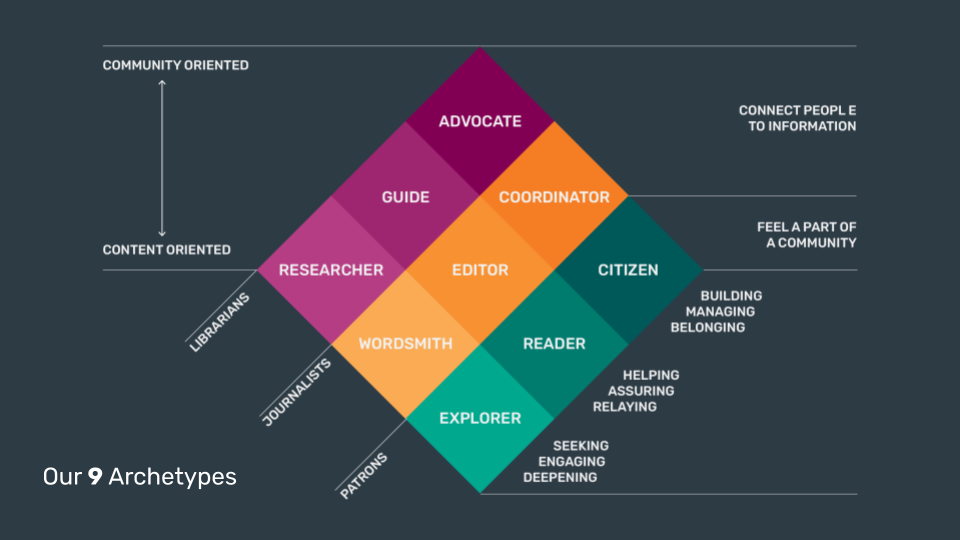

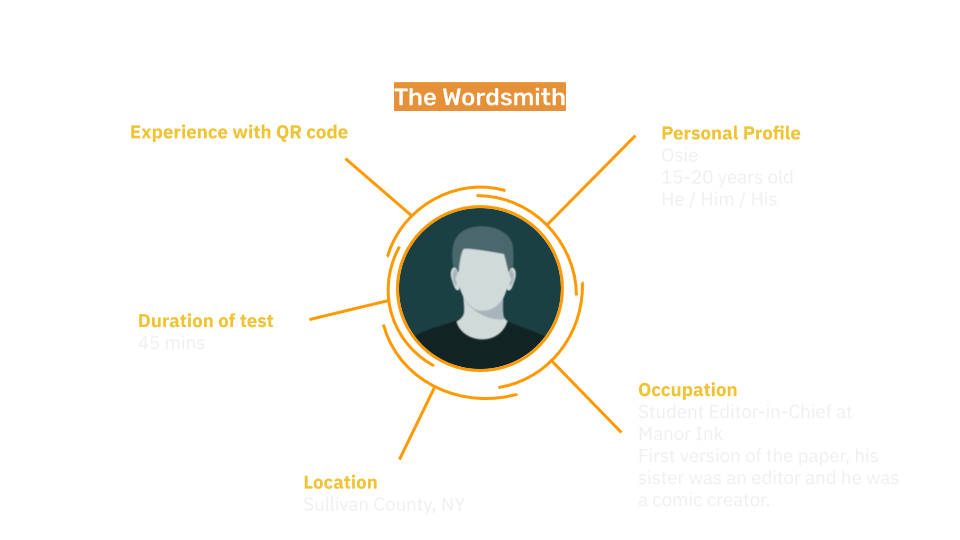

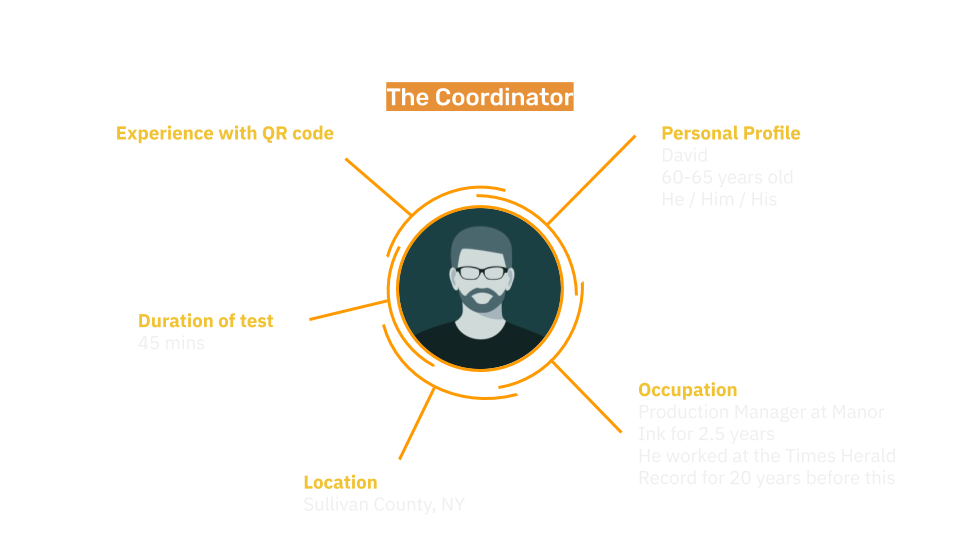

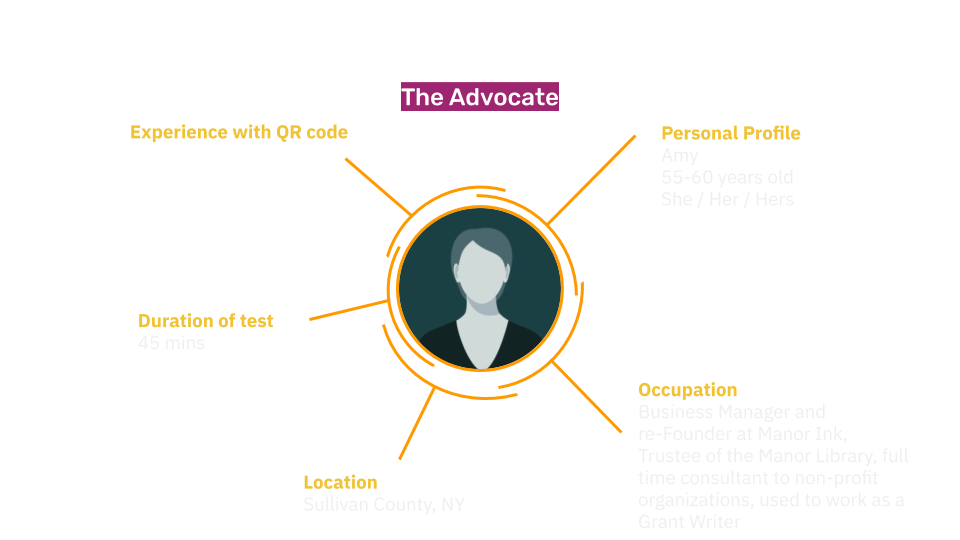

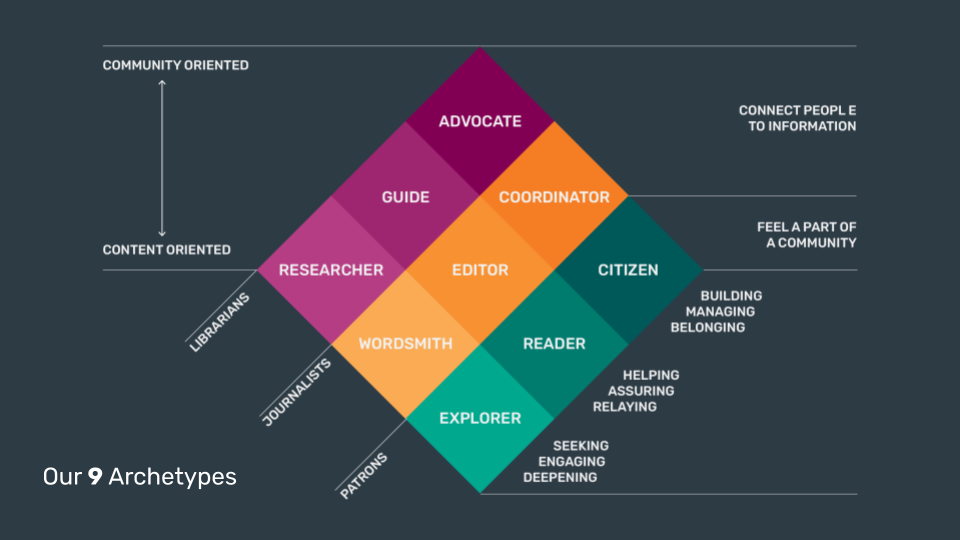

Our interviews have led us categorize the archetypes related to our project. We have 9 different types, ranging from community leaders to commutnity members as well as community oriented to content oriented roles.

PIT QUESTION

Is there an existing bias in the research? Who is being included or excluded?

This PIT question has led us to think about the different populations that have limited or underrepresented on the internet, or touristic towns that are overrepresented create an inequality of presence on the web. This has led us to keep asking ourselves: How do we conduct PIT research when google's top hits are almost all private interest sponsored results and articles?

SYNTHESIS

PIT QUESTION

What is the larger systemic issue where the problem sits? Are your solutions butting up against larger societal

issues? Have you uncovered any areas of exploration? What more research might you need to do to learn more about these areas?

Building trust is a crucial factor which varies, but still exists nevertheless as a relevant problem no matter the size

of the newspaper. In an era of fake news, people are losing their trust in news organizations and the accuracy of spread knowledge. Although our research about Livingston

Manor has shown us that there is a level of trust between the community members and the town’s only newsroom, more research about other towns is needed since this is a town-based

project.

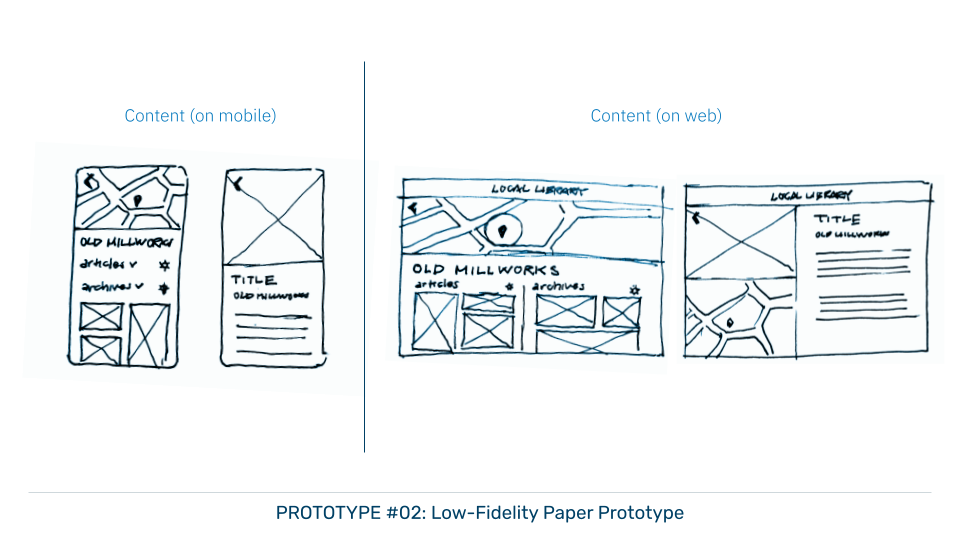

User Journey Illustrations

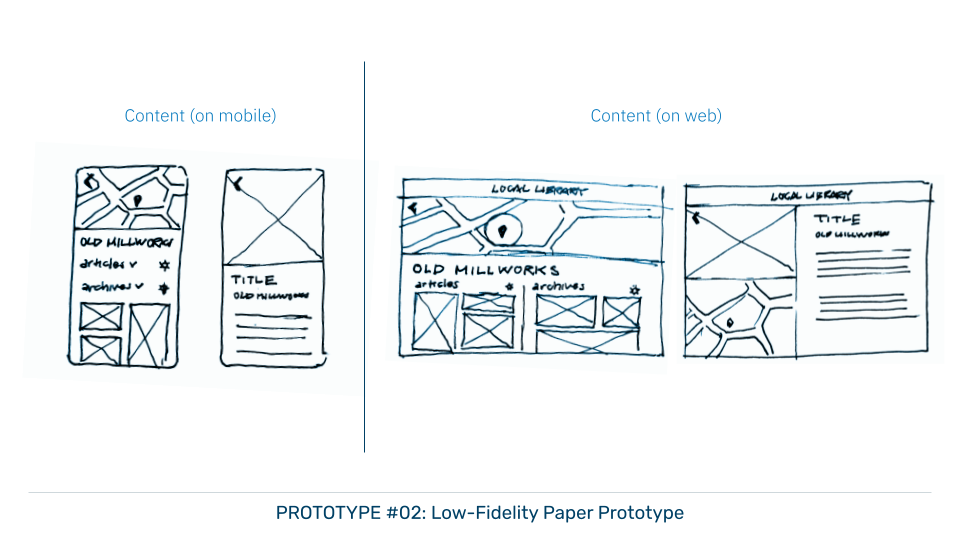

Initial Mockups

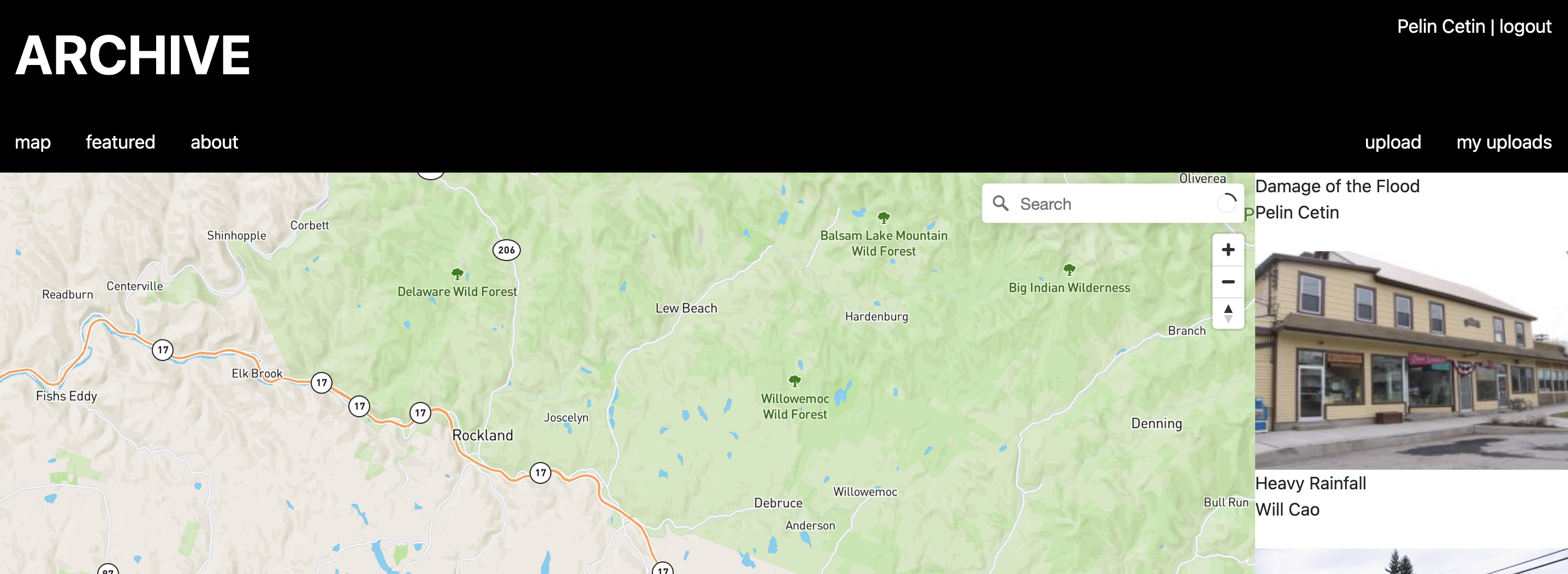

SPATIALIZING NEWS: GEOLOCATED INFORMATION

Mid-fidelity Mockups

Technical Design

The languages used for the website are: Javascript, Jquery, CSS, HTML

The libraries used for the website are: Mapbox & Flask

Visual Design

What does this test capture or not capture? What is the value system implied by the test?

The type of content share on this kind of platform came up during our multiple interviews and class discussions. The idea of filtering and editing comes with great responsibility. Who can moderate the content? And in what basis/guidelines? Where do you draw the line between opinion-based social network and a news article? An editor role would probably be necessary to curate any news.

TESTING

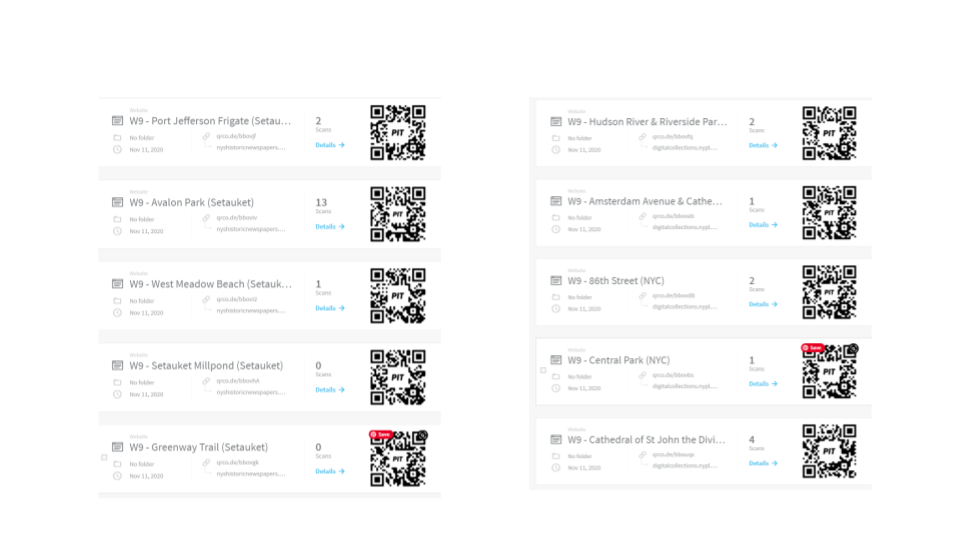

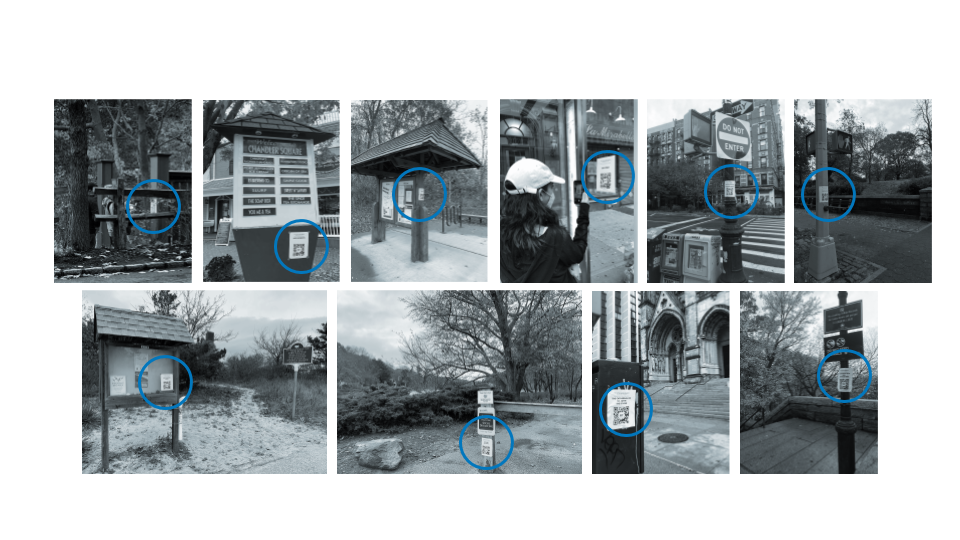

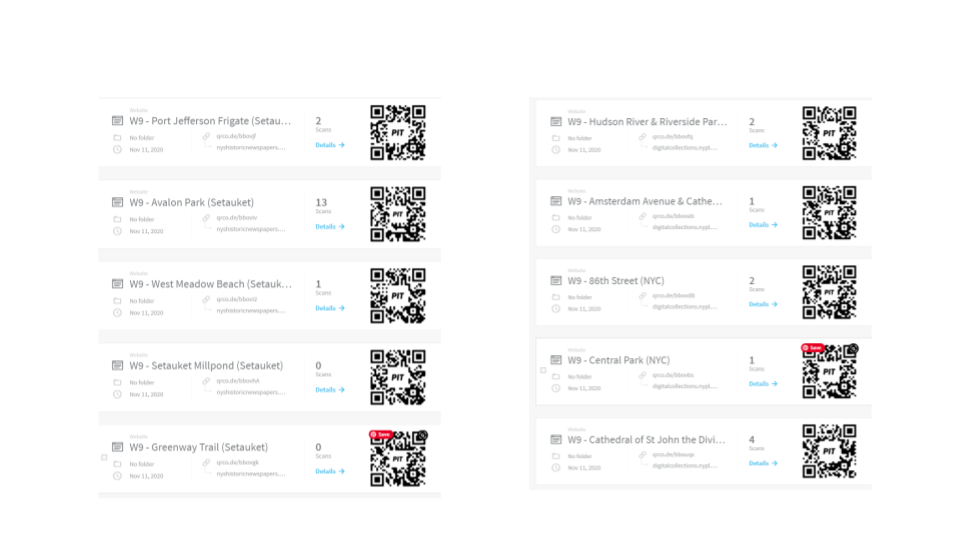

QR CODE TESTING

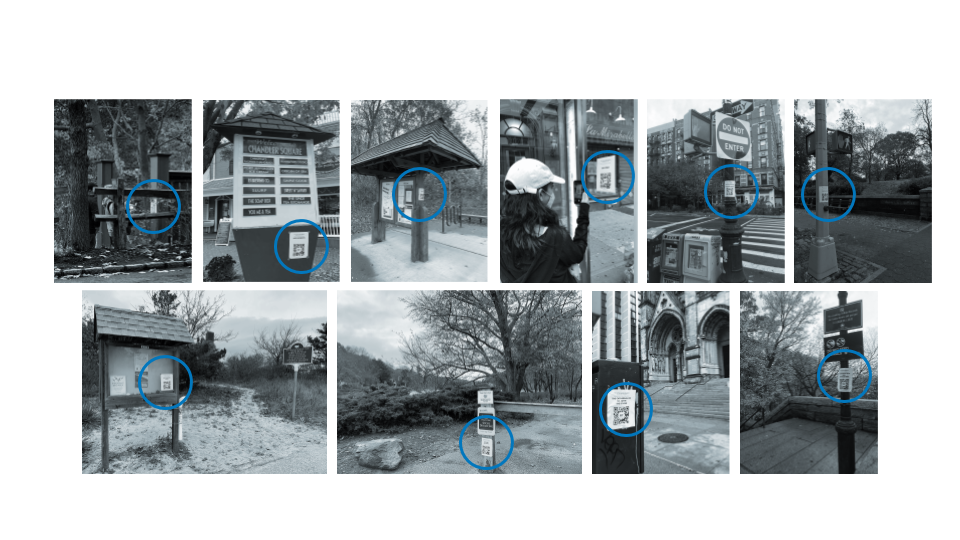

We tested the QR code aspect of our project in multiple locations. First in the Upper West Side in New York City,

then in Stony Brook, Long Island.

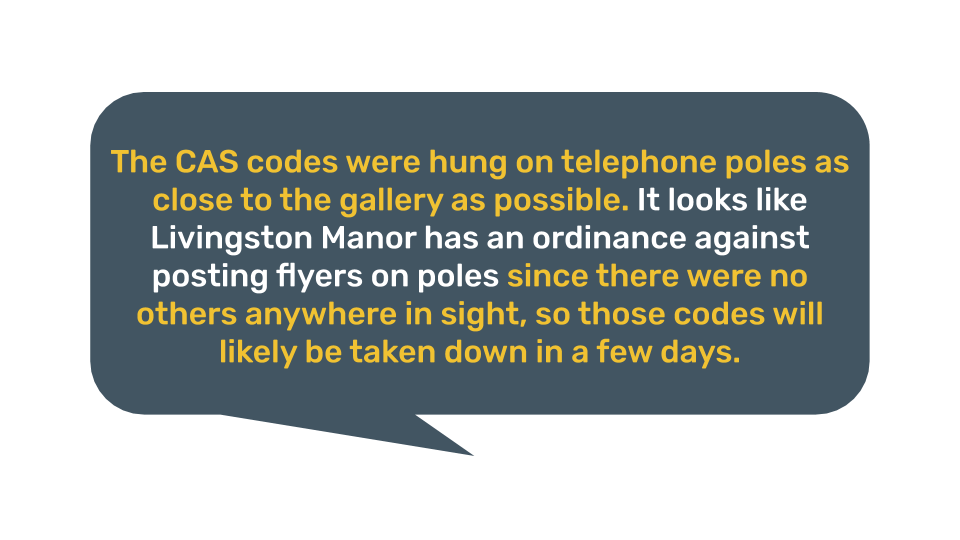

We then tested on our target user: residents of Livingston Manor. We were able to do that test thanks to our friends at Manor Ink, who generously agreed to hang our posters in their town.

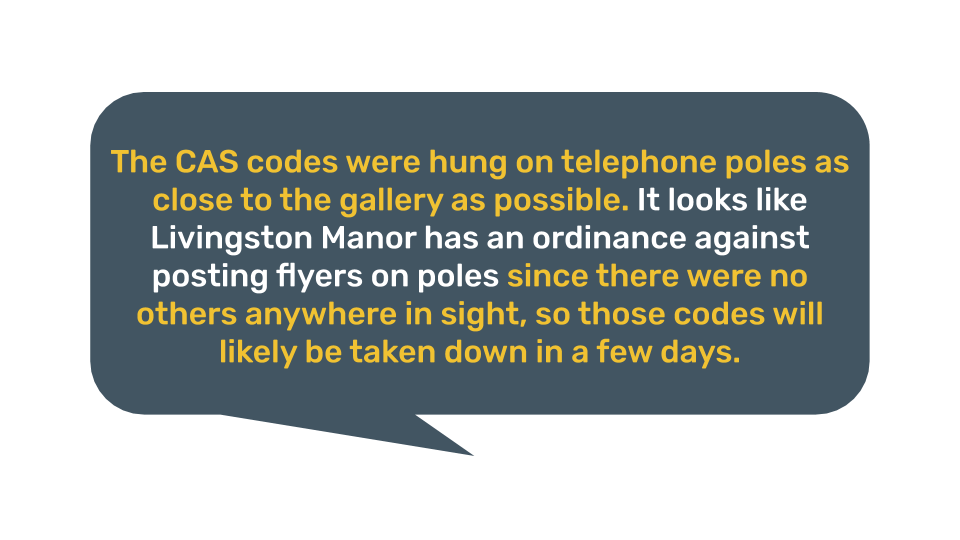

Photos of QR code posters in Livingston Manor in three different locations: Beaverkill House Park, CAS Gallery and Manor Park.

What risks might not be encompassed by your prototype?

If we are user testing on Livingston Manor, we won’t be able to directly apply our prototype to the community members, we will have to do it through a third party. We might have gotten different results if we had conducted the testing more precisely

and accurately.

Have you identified the questions and risks most relevant to this population?

The use of a new technology (in this case, the QR codes), is not very popular in Livingston Manor. This led

us to think of how much PIT is teaching a community how to use this new technology. We discussed an awareness strategy to launch our project in this town.

The posters would have to be recognizable, published around town, and spread by word of mouth.

The above video is an example of how a user would use the website. There is also an admin access,

where the admin can approve or reject an uploaded photo. There are guidelines for the picture verification, and the admins will not approve of a

picture that’s not appropriate for the project.

A self sustainable PIT project is not impossible but it is not always favorable. An editorial process must exist

to filter and preserve the quality of the project. This opens up questions of responsibility, guidelines, subjectivity. Who should get to decide on these principles?

Any PIT project will have to face this issue, whether related to newsrooms and libraries or not.

In this particular project, the library, being a source of trust in the community, acts as the moderator. It plays a neutral role. respecting the content and staying inclusive at the same time.

PIT DEPENDS ON PEOPLE

If no one is available to employ the capabilities that new technology brings, the technology will not be useful. PIT is dependent on the champions in the community that are already promoting public interest, whether they are editors, activists, or reference librarians.

SEE BEYOND THE SINGLE TASK

Communities are complex, and one need often overlaps with another. In creating our prototype, we found we had to account for the uploaders, the editors, and the media consumers simultaneously. We could not focus only on their success in uploading a picture or filling out a form. Instead, we had to find ways to enhance how each user group communicates with one another.

ABILITIES IN THE SAME COMMUNITY CAN DIFFER WIDELY

We found that members of the same community may not have the same ability to navigate technology as others, such as its older and younger generations. We tested on different age groups of community members for this reason. We also found that younger generations often helped older generations to acclimate to new technology, an undervalued means of strengthening community bonds.

HELP ONE COMMUNITY AT A TIME

Early in our process, our focus was on creating technology that was scalable, to be useful and relevant to all of the communities we spoke with. We realized for our PIT prototype, it was more important to focus on one community’s needs, to ensure that all the nuances of this community’s needs were accounted for. Moreover, we found that components of our solution that had great results in some of the communities we tested within, such as the QR codes, did not have good results in other communities.

We would like to thank everyone who helped us on this journey.

Osie, Manor Ink

David, Manor Ink

Amy, Manor Ink

Charlotte-Anne, NOWCast

Savannah, KCQ

Talia, KCQ

McArdle, Local Lives

Justin, Amazon Inc.

Julia, Cook Memorial Library

Ellen, Brown University

Isaac, Columbia University

S.T., Columbia University

Sarya, Teacher at public school

Karim, Business Analyst

Finally, thank you to the COMS 6998 Advanced Web Studio Design Teaching Staff.